It’s been a while since my last post – there’s a good reason for this. Well, a reason anyway. I have a 90% written post which I have been mulling over for a long time. Because I haven’t felt comfortable with it, or finished it, it’s been a bit of a logjam for the blog (a blogjam?), with subsequent blog posts and ideas taking a back seat. So, rather than abandon it, I’m going to smuggle that post, untitled, into the next two paragraphs, then move on with this post. Let’s make this blog more about data visualisation, and questions therein, than about me. The eventual point to this post might not be clear until much nearer the end – stick with me!

The title of the aforementioned previous post was going to be “So how on earth did I become a Tableau Zen Master?” because last month, that happened. You can learn more about the Tableau Zen Master scheme here and the three elements that comprise selection to become one: Master, Collaborator, Teacher.

I’ve done a lot of thinking about it – it really has left me scratching my head for a few weeks despite all the congratulations and positive comments I’ve had, and I’m still not sure I know the answer to the question of how I became one. But I’ve started do get through the impostor syndrome and I’m going to embrace it. Though I can’t mention impostor syndrome without linking to fellow Zen Bridget Cogley’s post about it – just promise me if you read it you’ll come back here. Get engrossed in her blog and you won’t feel the need for mine or any others … Anyway, there are only just 30 Zens in the world, and I know that I am not one of the top 30 most technical users (I don’t know how you’d quantify it, but I’m patently not even anywhere near the top several thousand). But I’ve come to realise it’s about more than that. I have to assume that people respect and like what I do and the manner in which I do it, share it and evangelise it. And more often these days I’m seeing amazing work which adapts and improves on mine, with three crucial words that I’ve grown to love: “inspired by @theneilrichards“. Hopefully I can embrace it with humility, because even by cutting a long introspective blog post down to two paragraphs I can still leave enough space to say a huge thank you to those who nominated me and those in Tableau who appointed me a Zen Master. Those who have given advice have all essentially said the same thing, to me and to all new Zen Masters: “Keep doing what you’re doing”. So, I will. For me, that’s visualising a lot, speaking a lot, and blogging a lot.

So, perhaps as a result, I’ve been prolifically visualising. Two visualisations followed around last month’s Winter Olympics. First of all, my response to a #MakeoverMonday challenge to visualise historic medallist data was this joy plot below (and here’s more about joy plots)

Hot on the heels of that was my curling-themed visualisation, which I’m obliged to figure and self-promote, because it has been featured as Tableau’s Viz of the Day

Both of these are example of the direction in which I’m continuing to head (especially in the visualisations I choose to promote, anyway) of design driven data. Focussing on design elements first and choosing the data, whether it be the overall dataset or the elements within that dataset, to represent the visualisation choice. The joy plot in particular was a case in point. Partly liked and partly disliked/overlooked, I had one comment which described it as a beautiful work of data art. That continues to be my aim, and because I don’t claim it to be an analytical piece, that’s the feedback I can choose to included while ignoring those who dislike its analytical weaknesses!

The curling visualisation has received a bit more acclaim and is another example of design driven data that I’m really pleased with. It doesn’t tell the story as well as a bar chart or heat map of who is the most accurate, most consistent or has the greatest tendency to curl anti-clockwise (though you can explore and find all of those things). Yet, (am I allowed to say this?), it looks quite cool!

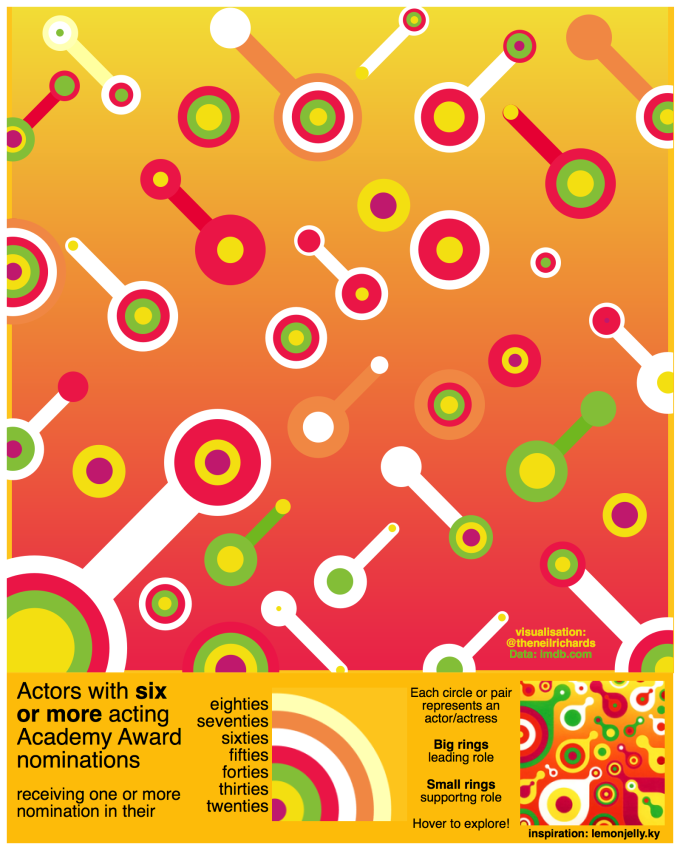

And, as I returned to my theme of #AlbumCoversAsDataViz (a niche hashtag, I’ll be first to admit), I was delighted to release this visualisation around the theme of Oscar winners and nominations. I’ll feature this without comment below, only suffice it to say that I’m delighted with the outcome of this particular creation – the data sits really well with the design and the user can explore Oscar nominations of the most successful actors and actresses through history. A nod to Tableau’s “Viz in Tooltip” feature which really enhances the user experience of, shall we say, less conventionally-designed visualisations like this one:

And now we come to my latest visualisation which has inspired the question and discussion around this blog post (“at last”, I hear you cry). This makes over a chart depicting the number of pets of different types owned in the UK, and purports to show the same information.

Now, armed with the information that there are 15-20M fish kept in ponds in the UK, 15-20 M fish kept in tanks, 8.5M dogs, 8M hamsters, 900K rabbits etc., how would you report that if you had to disseminate that information (a) to your boss and (b) to the general public in an accurate and visual way? There’s never a correct answer, but I would hope that you would think or at least strongly consider the answers: (a) a bar chart and (b) a bar chart.

My map exorcised (some) readers, and here are some of the reasons I think why:

- It’s obviously not a map. It’s perhaps unfair to use the word “obviously” here, but do people really think that all dog and cat preferring areas are always diagonal to each other and never meet? That people who own fish live in the sea? It doesn’t take much to realise that, but that time is longer than many people’s attention span. I’m not being derogatory here, because I include my own attention span in there too. The medium of twitter and fast paced snippets of social media information mean that people need to understand things instantly, and this is true. Rather than make the leap, people told me they just assumed there was geographical relevance, or directly asked me if there was any geographical relevance to placement of the animals. So it’s a bad viz.

- Readers can’t make comparisons. Are there more cats than dogs? Hamsters than horses? Even if there are no geographic meanings to placings of coloured dots, we can at least make comparisons if we, say, group the animal types together. As it stands, it follows no Gestalt principles

- It’s not a bar chart

But here are my responses and why I think people may have taken this a bit too seriously:

All the points I mention, to me, make it obvious enough that it’s not to be considered a map. I even had one response (not from a UK reader) who had no idea it was map-shaped in the first place until they read some of the tweets debating it! The key thing to me is that my audience in this case is not people who want to know the key take out information quickly. It’s not a key report for Pedigree Mars telling them in which areas they should focus dog food over cat food. It’s not a report for Pets at Home telling senior Directors where they need to think about opening a new store. It’s not a journalistic piece explaining the prevalence of dogs over cats in the UK overall or determining the regions where cats outnumber dogs. It’s a visualisation with all pet types in correct proportions, to catch the eye by being arranged in the form of the UK’s land mass and surrounding sea (with apologies for casting the Republic of Ireland adrift). It’s a visualisation that could (though I’m over-selling it here, I’d be the first to admit), be used in poster form, with a certain amount of improvement and embellishment. My audience is people who like visualisations and are interested in the wide range of visualisation skills, possibilities and choices in the field. Aficionados of data art as well as visualisation. By definition, people who don’t just consume visualisations, but come onto twitter and other online spaces to enjoy, search for and discuss visualisations.

I wanted my visualisation to be noticed, and talked about (albeit positively would have been nice!). Perhaps it doesn’t help that one of my favourite popular artists (MC Escher) sets out to deceive, ironically perhaps using land, air and water based animals (below: Sky and Water I, sourced from Wikipedia). I love to solve word puzzles or chess puzzles, but in addition to that I enjoy creating them – lead the brain down one direction, make it think, and then find the correct path. Inadvertently it seems I’m doing this, up to a point, in my visualisations.

Important to me is that I wanted it to be accurate too, which is why, despite being happy to discuss its pros, cons, good points and bad points, I do fiercely defend it as a data visualisation and not just a pretty picture (an accusation levelled at it in some of my feedback, even by those who defended it: “It’s lovely but it’s just a picture, you don’t need to defend it!” to paraphrase one discussion). OK, it’s a picture, but using the medium of data, portrayed accurately if not intuitively. One accusation against design-centred visualisations is that they are “vizdata” and not “dataviz”. Since both are made up words anyway, I’m not sure that matters, but do they have to be separate entities? Can a “vizdata” (ugh!) not be a particular type of dataviz? A subset?

So for these reasons I spent a lot of time on design. The total number of pets I had in the data was 55.5 million. I could represent this with 555 separate circles, 100K pets for each one. Schoolboy maths (prime factors) led me to a rectangle of 37 by 15 giving exactly 555 squares. Could I then fashion a map of UK so that 350 squares were filled with alternating fish and 205 with land-based pets? It became a low-tech exercise using an outline map of UK on half of my screen and colouring in square in Excel on the other half, counting exact numbers so that all correspond exactly with the data. A lot of painstaking tweaking was done to get the 350/205 ratio exactly right, before the land-based pets were included.

Yes, the placings are arbitrary. Only I know that I put a reptile on Lizard point. A caged bird on Canary Wharf (though London is big enough also to include Isle of Dogs and Catford). There’s a rabbit over the Nottingham suburb of Bunny. The reader knows none of these things but I create data visualisations for fun, so I’m going to have fun including these things. If anyone can tell me why I deliberately put a hamster on the East Anglian coast then (a) I’m amazed anyone’s still reading this far down and (b) I will think of a suitable prize for if we ever meet at Tableau User Groups in UK or Conferences in UK/US this year!

It’s important to note the context of visualisations and I think that’s where the reaction to this visualisation has arisen from (I deleted the words “that’s where my mistake was”)

- My visualisation looks like a standard visualisation, and follows all the best principles. People really like this, why wouldn’t they? Illustrated by the purple bar chart on the left

- My visualisation looks nothing like a standard visualisation, more like data art, and doesn’t follow many of the best principles. Not everybody’s cup of tea, but people like this and don’t mind doing work to understand the viz; and those who don’t like this respect it for what it is. Illustrated by my album-cover inspired visualisation on the right.

- My visualisation looks a fair amount like a standard visualisation, but actually it’s ignoring principles for design’s sake. This is what gets people cross – they have to think contrary to first instincts. They probably still invest no more time understanding it than (2) above, but feel they’ve been tricked and shouldn’t have to.

If you aren’t taking a particular visualisation seriously, if you’re in the middle of the Venn diagram above, focusing on design over data analysis, then be prepared for a reaction from those who interpret your design differently on first viewing. I received lots of feedback for my visualisation – because I’ve paraphrased it in this post throughout then I haven’t sourced the name of each person, but most thanks are due to Mike Cisneros for being the harshest critic, and for taking the time to explain why, by verbally framing the explanation above. If you get criticism which is good, bad, or indifferent, you listen: Mike is that knowledgeable. The easiest way to demonstrate a good, correct, inclusion of principles, is either to demonstrate their inclusion and how it leads to a good end-point, or to demonstrate their lack of inclusion and how it fails to do just that. So you can argue that I’ve done the latter nicely by my ignoring Gestalt principles in order to focus on a design.

Makeover Monday has gone from strength to strength and one of the corollaries of that is that it has become a go-to weekly hit for expert advice and community feedback on the best way to visualise each week’s dataset. Perhaps this context is a particular reason why people might feel that this particular initiative should be taken seriously. I would counter that argument (rather than disagreeing with it) by saying that for most people Makeover Monday is done as a personal project outside of work. I use it as a freely available dataset, a burgeoning community, a chance to practice new skills and a chance to think of new design ideas. You can’t do that every week with bar charts. I continue to talk at venues round the country about its benefits but I do so from my own perspective, how it helps your skills, experience and portfolio grow. There’s nothing wrong with taking it seriously, framing every submission as something you might present to a client, but there’s also nothing wrong with not doing so.

Being a Zen master might mean that I have more responsibility to teach, for people to take a lead from me. But the best advice I also had on being a Zen master, is to keep doing the same stuff I’ve done up to now. I’m no better at bar charts than most of you reading this, but I’m quite good at playing with Tableau and talking/writing about it. And so in a roundabout way I’ve discussed, if not answered, this post’s question, even managing to crowbar in some Zen relevance!

I never shy from discussion over visualisations (if I did then this blog would be pretty empty!), and if this alone is enough to convince you to stay away from visualisations that looks like maps but aren’t then I’ve done my bit.

5 Comments